ART CITIES:Venice-W.W.W. What Walls Want - Emil Lukas Reference

"shaped hum" referenced at:

http://www.dreamideamachine.com/en/?p=36553

10 things to do in Venice out of the Biennale

#2 Art and Architecture

The End of the Utopia , an exhibition that brings together two artists from the highly geometric figure: Emil Lukas and Jacob Hashimoto . The very linear layout succeeds in creating a dialogue between the contemporary sign with stucco building Flangin the Campo San Geremia. But the works of Beverly Barkat for the exhibition Evocative Surfaces was inspired by the halls of Palazzo Grimani , one of the few Renaissance palaces, which displays his work.

http://living.corriere.it/tendenze/arte/10-cose-da-vedere-a-venezia-fuori-dalla-biennale/

"The End of Utopia" - Emil Lukas, 2017

"The End of Utopia" - Emil Lukas, 2017

video Michele Alberto Sereni, courtesy Studio la Città - Verona

“Jacob Hashimoto and Emil Lukas, two internationally recognized American artists, have been invited by Studio la Città Gallery to stage a site-specific show in Palazzo Flangini reflecting on “The End of Utopia”. As we move deeper into the Anthropocene, the cost of our ascendancy is becoming clear. Decades of environmental exploitation have left us perilously balanced and wavering on every side: political, social, economic, natural, technological, and ecological. As many observers of the Anthropocene have noted with apt unease, humanity itself has increasingly become the perpetrator, rather than victim, of planetary chaos.

Emil Lukas’s work occupies the first-floor of the space. Lukas has created three separate, but interwoven, groups of work: “Lens,” “Puddles,” and “Threads.” At one end of the vast gallery, 650 aluminum pipes are assembled into a giant lens of sorts. Through its side-by-side tubes, the concave, almost iridescent sculpture affords a vista that moves with the viewer according to his or her position. From the right angle, the lens focuses and isolates the viewer, distilling the experience of the artwork to a single, fundamental perspective—the watchman’s post in the Panopticon. While Lens speaks to the seductive nature of observation and surveillance, the Puddle paintings are vast microcosmic landscapes that, conversely, conjure an unobserved, almost geologic progression of time. More like sculpture than painting in many ways, these works feature surfaces pulled into funnel-like concavities by clusters of taut thread. Lukas then allows masses of paint to collect in these depressions, letting the pigments separate, reticulate, and form stratifications. As the paintings dry, the pigments leach through each canvas, staining and revealing the surfaces’ buried histories.

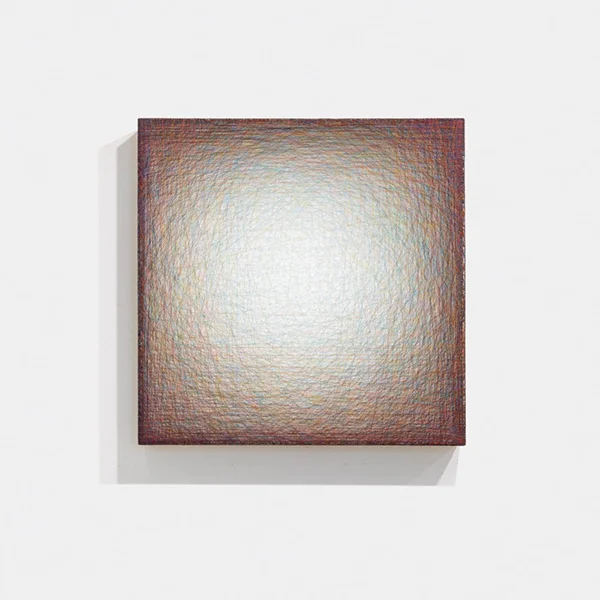

Lukas’s Thread paintings are delicate overlapping skeins of colorful thread, anchored to the sides of idiosyncratic wood stretchers that frame uneven, pockmarked white-plaster backing. These threads cross each other most densely around the stretchers’ perimeters, leaving the centers of the constructions relatively spare. The effect of this patterned density creates a powerful optical illusion of volume from a distance. As the viewer approaches each work more closely, its skein of threads becomes apparent, and a delicate atmosphere, shifting over an alien landscape, is revealed.”

Emil Lukas, Weaving Art With Nature - BLOUIN ARTINFO

"For Emil Lukas latest eponymous exhibition, the Pittsburgh-born artist brings his layered pieces of thread and larvae paintings to Sperone Westwater Gallery in New York City."

Emil Lukas at PAFA: Magic made from cardboard, string, and bubble wrap

“Michael Lieberman is wholly absorbed by the pulsing, near-celestial effect of Emil Lukas’ work, and calls this show a can’t-miss.”

“Five works of art comprise Emil Lukas’ exhibit at PAFA’s Morris Gallery. Yes, five. And not only are the pieces awesome, but their spare presence makes the austere, skylight-lit Morris Gallery look stunningly beautiful. Okay, the highlight of the show, the sculpture “Large Lens” pictured here, composed of glued-together cardboard tubes, commands the gallery, and it is huge, a good 10 feet in both the vertical and horizontal, and two-and-a half feet wide, and it is curved like one of those giant, otherworldly communication satellite dishes you see here and there. And notwithstanding its size and pedestrian components, “Large Lens” is an enchanting plaything—more on that below. But the four other works by Lukas, though unequal in size, are equally formidable and engaging. So, what you have here is a gorgeous skylit gallery and five totally absorbing works of art which must be seen and experienced to be believed. I should leave it at that.”

To see the full article of Michael Lieberman's review. Please follow the link below.

Emil's Vimeo Profile

Take a look at the most recent sculptures as laid out in Emil's studio in Stockertown, PA.

ArtNet News - "Emil Lukas’s Abstract Larvae Paintings Are Physical Feats of Creation"

Full article can be found here: ArtNet News

In case you missed it, the Farmers’ Almanac, which for 2013 correctly predicted a colder than usual New York winter, delivered a disquieting forecast for this summer. “Exceptionally hot” is the outlook for much of North America, with the Northeastern region of the country predicted to be “oppressively humid, wet, and thundery.”

For Emil Lukas, this may not be unwelcome news.

A sculptor and process painter who once divided his time between a Harlem studio and one in Stockertown, Pennsylvania, he now maintains two studios in the Keystone State, and in one of these he creates what he calls Larvae paintings.

The paintings are not representations of larvae, as you might think. In this case, the actual fly larvae of, say, Calliphora vomitoria, the blue bottle fly, behave as tools of his trade. They are what Lukas uses instead of conventional paintbrushes (not exactly Yves Klein’s “living brushes,” but hey).

It is February 22nd when I meet the artist at his downtown gallery, Sperone Westwater, on a bright Saturday morning. The Bowery neighborhood is on the march—to yoga, the nail salon, the Apple store, Falai. But in here, in this space, there is a slow heartbeat, thankfully.

This is the final day of Lukas’s solo exhibition, which opened on January 9th. On some walls hang his Thread paintings—works with colored polyester thread (physical, structural, pictorial lines) pulled over painted wood frames and “locked down” (as he puts it) on the edges. On other walls hang the Larvae paintings. It is these that hold my attention.

Lukas and I discuss the role that the weather plays. Consistently hot weather is essential to the work; it’s what motivates—literally—the insects during their residency at his Stockertown studio. The temperature determines the speed of what Lukas refers to as his two-month production season. During the doggy days—usually August and September—when the weather is the hottest, the larval life cycle is the most rapid.

Months before the larvae arrive, however, Lukas is hard at work, alone, during dark afternoons. Round about mid-February, he begins fashioning wood panels and stretching canvases. Then he adds many layers of gesso, applied and sanded many times, to approximate a surface as smooth as paper.

Come May (and crocuses), he’s applying acrylic paint and introducing color and composition. During these early days, Lukas estimates that he applies between 30 and 50 layers of paint using everything from rollers and all manner of fibrous brushes to splashing to spraying. He tints the primers, puts in lines or circles—to produce a set of compositionally unique “underpaintings.” One might be warm, another cool, another congested, another light. “I want the paintings to stand in relationship—I want the paintings to stand apart from one another as early as possible, before the larvae,” he explains.

And then, come late June or July, Father Nature sets his schedule, and Lukas is in his hands. The anticipation can be uncomfortable. Lukas says he asks himself a battery of questions: “Is it gonna be hot, is it gonna be cold? Is it gonna work? It is not gonna work? Is it gonna be a good week or a bad week? Am I going to paint thisthis week, or am I going to paint something else this week?”

Any day, Lukas must paint when the weather is hottest because a surprise cool front might always arrive unannounced. “It becomes a real drain by the end of summer,” he says. “It’s fantastic, but after a while, you definitely need a break. You don’t mind it being seasonal.”

Interior view of Emil Lukas’s studio barn.

Photo: Zach Hartzel, courtesy the artist and Sperone Westwater, New York.

How Lukas lures his blind collaborators is his own private, ugly secret about what he terms “the science” of the process. He won’t discuss that part.

“There’s no other insect that makes sense to connect these paintings to,” he says. “What larvae do, why and how they are—it’s the perfect connection.”

But come on, I say. Why flies?

“What I’m trying to achieve I feel can only be achieved this way, and it’s something that I’ve worked for 20 years to develop,” the artist states.

Twenty years? Actually, a few more than that.

One night during the late 1980s at his Harlem studio, Lukas casually murdered a pesky fly and left it overnight in a four-inch puddle of paint on a piece of cotton paper. The following day, much to his surprise, he returned to a drawing suggestive of a pattern of electricity or lightning. It turns out that his victim had been a life-bearing fly, carrying larvae, and the tiny life forms had tracked paint all over the paper.

Lukas was intrigued and began to conduct research and experiments with many organic materials, such as mold, seed germination, spore drops, carbon, and fat. Only flies (he has not worked with other insects) achieved the status of full-blown obsession and then: art.

Okay, but still: Why flies? (Personally I find them disgusting.)

“I’m after a mark that has intention,” Lukas tells me. “An intention then goes to rhythm, the rhythm goes to repetition, repetition starts to look like the human hand.”

Now I’m beginning to understand.

He continues: “There’s a formula that is very difficult to find when it comes to this intention, the human brain, and patterns. This is a link to a device”—the device being the fly larvae—“that allows me to work in a very clear and deliberate intention without the pattern subscribed by the human brain.”

Of course, Lukas sets countless parameters of play—including lighting (natural, artificial, direct, diffused—the larval visual system reacts to all of these), vibration level (the paintings are on wheels), density of color (Lukas uses a mixture of ink and paint, both water soluble), and the level of wetness of the canvas itself.

The process allows him “to direct a painting that has millions of lines, and the lines don’t fall into the pattern that a human would have if a human made a painting with millions of lines. That’s one of the things I really love about the paintings.”

I suppose I must love that too. I lean in towards one, then out. It’s wider than I am tall. A wiggly line reminds me of a river seen from 35,000 feet in the air. Hm. Now I inspect a coil. Could a human brain produce that design?

Lukas describes how he intervenes at one moment of the flies’ life cycle to get this effect. “From the time they are larvae until the time they pupate, I intervene at this little interval,” he says. “We make these paintings, and then the larvae are outside again; they hatch, they fly away—they fly all over the community. There’s something that’s very significant to me. There’s a moment they come in, there’s a moment they go out; and this is what we make.”

He and I pause, we human-brained beings, and look at each other.

Emil Lukas, Rain (2013)

Photo: Courtesy Sperone Westwater, New York.

One painting, called Rain, has an underpainting of butty-day white; the foreground is a brambly tangle.

“I want people to look at the paintings, and I want them to think about them like calligraphy or like lightning or roots or the history of painting being applied to a canvas in the many ways that other artists have done it,” he says.

But none of this occurs to me. Thoughts are not formulating. Instead, I begin to peer into the abundance of tangle. The mind-feel (for lack of a better phrase) of a small child in the woods comes over me. Somewhere beyond that derangement of lines, in the center of the canvas, is a place akin to the Platonic ideal of a clearing. I feel as though I can step into the canvas, away from grownups into a safe place of my own. No flies are here.

I look at Lukas. By virtue of his curiosity, sparked all those years ago in Harlem, he has landed me somewhere realer than fiction. It’s possible the expression on my face tells him he has accomplished something unusual.

“Randomness,” he mentions, “is a difficult pursuit.”

Whitewall Magazine - "MARGARET GARRETT, EMIL LUKAS, AND MELISSA MEYER"

Full article can be found here: Whitewall Magazine

Then there is the truly elegant display of work from the last year by Pennsylvania-based artist Emil Lukas at Sperone Westwater Gallery. Although not widely known in the United States, Lukas has shown his work throughout Germany, France, Switzerland, and Italy, including as part of the renowned Panza Collection in Varese.

Lukas “paints” his so-called thread paintings, to which half of the show is devoted, by drawing intricate skeins of various colored polyester threads across his canvases.

(The show also comprises one other series, what Lukas called his “larvae paintings.” Jeff Koons’ dozens of studio assistants cannot compare to the millions of fly larvae Lukas lets loose to eat patterns as they will into freshly painted canvas.)

These thread paintings can read like musical instruments, nearly throbbing with a tympanic tautness. Five of those on view have a glowing circle-within-a-square motif that seems to invert Anish Kapoor’s widely exhibited, seemingly floating, two-dimensional, fiberglass wall sculptures. The luminous orbs in these five works appear to be lit from within. Like James Turrell, Lukas can seem like an illusionist, optimizing light, color and the shifting angle of the viewer to create a unique and elusive optical experience.

Unfortunately, as Lukas said when we toured the gallery minutes before the show’s opening, “Historically I make work that is impossible to photograph.” He’s right on this count. No image I’ve seen has been able to capture either the ethereal luminosity or complexity of craftsmanship of the thread paintings.

In the exhibit’s accompanying catalog, Lukas noted that he was “first attracted to thread” when traveling in Germany in the late eighties where he remembers seeing huge racks with hundreds of spools in different colors on display in garment stores and drugstores. “The dramatic visual effect fascinated me.”

“For me the thread paintings are about color. They’re about compositions of color, light, reflection, and opacity. They’re much closer to formal wet-on-wet watercolor paintings than they are to anything in the textile field.”

That rings true, because despite the materials, there’s nothing artsy-craftsy about these works. If, like me, you’ve ever admired the artistry of a handmade drum or marveled at the inside of a piano, you will especially like Lukas’ work.